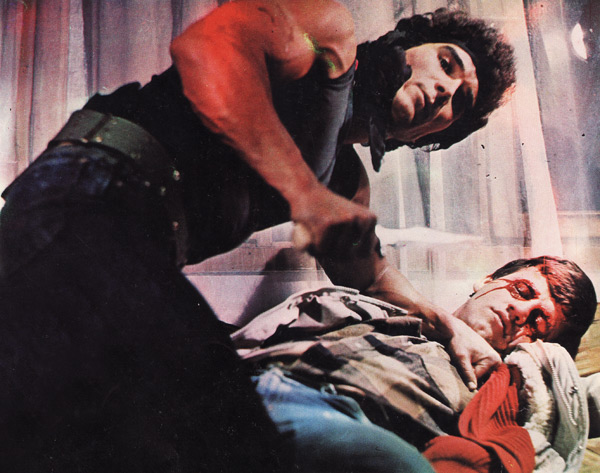

Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam AKA The Man Who Saved The World (Çetin Inanç, 1982) doesn’t make it too far past the endearingly handmade titles before it demonstrates the elements that gave it its better-known title, “Turkish Star Wars”. Edited into new Turkish scenes are newsreel clips of NASA rocket launches, instantly recognisable shots from Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (chopped from a print in a different aspect ratio from the rest of the Inanç‘s film – making the Death Star an odd shape), and identifiable footage from Sodom and Gomorrah (Robert Aldrich,1962) and The Seven Curses of Lodac (Bert I Gordon, 1962). The roguish leads, Cüneyt Arkin (Murat) and Aytekin Akkaya (Ali) are shown in space battle, their commitment to their performance overriding the viewer’s disbelief as projected footage from Star Wars cuts haphazardly between scenes behind them. Nobody in Lucas’ Rebellion ever had to deal with their spaceship appearing and disappearing around them, and even Luke Skywalker probably wouldn’t have dared flying backwards down the trench in the Death Star, even if it was oblong. But then daredevil Ali reckons the enemy are too sour-faced and he’d prefer “if some chicks with mini-skirts were coming”.

While the provenance of the visual effects is immediately and jarringly obvious, the soundtrack is equally dubious. The music not sourced from library stock is bastardised from an impressive array of high-profile soundtracks, including John William’s score for Raiders of the Lost Ark (The Raiders March and Chase Suite), Giorgio Moroder’s disco cover of the Battlestar Galactica theme, Ennio Morricone’s theme for the TV mini-series Moses the Lawgiver (Gianfranco De Bosio & James H Hill, 1974), music from Planet of the Apes, Moonraker and Silent Running, and then Queen’s score for Flash Gordon – a film which also provides key sound effects. Even JS Bach’s Toccata gets a showing. Such audacious theft cannot help but overshadow the homemade costumes, mannered stunt work (particularly Arkin’s trademark trampolining) and lunatic storytelling that the film otherwise consists of, but Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam is still more entertaining than The Phantom Menace.

Such pithy comparisons have revived international interest in a peculiar sub-section of Turkish film that thrived domestically in the late 1970s and early 1980s, of which Turkish Star Wars is only one among many. There are now countless blogs and webpages dedicated to lists of bizarre and poorly-made foreign versions, some official, some not, of Hollywood films. Usually light on context and high on derision, these articles have nevertheless brought to light a whole spectacular genre that may be described as Turkish Remakesploitation.

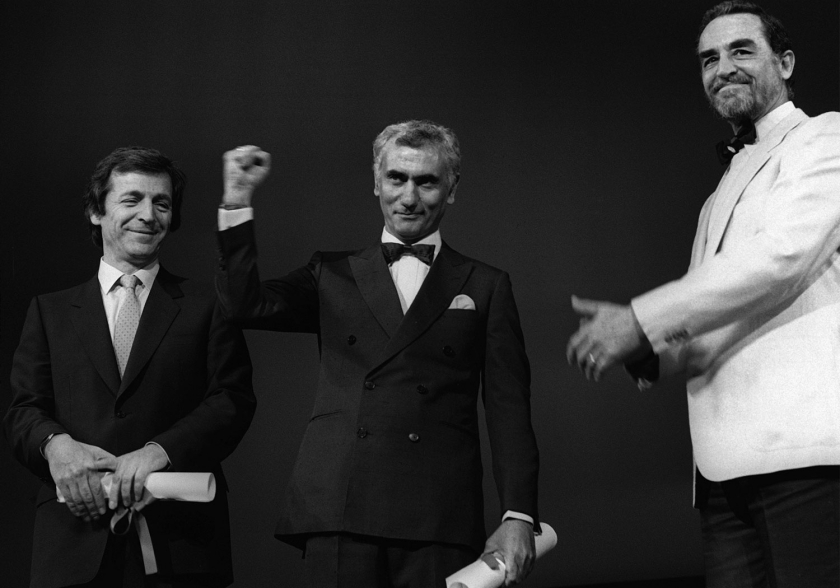

Most of these films were made during a particularly tumultuous period for the Republic of Turkey that saw the country experience the third coup d’etat since its formation in 1923. The 1980 military coup followed coups in 1960 and 1971 and brought a temporary end to violence but also ongoing political instability that has continued to the present day, with the country engaged in a long struggle towards multi-party democracy. Contrary to some reports, there was no general ban on American films in Turkey, even during the period of the military coup (from September 1980 to November 1983) beyond the individual bans on Midnight Express (Alan Parker, 1978) and A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1973). The more serious censorship affected domestic films and directors, most famously Yılmaz Güney who, in the middle of this period, orchestrated the production of Yol AKA The Way (Serif Gören, 1982) from a Turkish prison cell. One of the biggest movie stars in Turkey (of a rough and roguish type similar to Arkin), Güney was also one of the most politicised, first jailed in 1961 (for publishing an allegedly ‘communist’ novel) then again in 1972 and 1974. Escaping prison in 1981, he completed Yol in Switzerland and it went on to win the Palme D’Or at the 1982 Cannes Film Festival. Exiled in Paris, Güney died of cancer in 1984 and he is now internationally renowned as a key figure in modern Turkish cultural history.

However, the kind of low budget oddities that decades later would become known as Turkish Jaws, Turkish Dirty Harry or Turkish Exorcist, among many others, belong in a world parallel to the politically and socially conscious filmmaking of the likes of Yılmaz Güney. Even filmmakers sometimes mentioned in the same breath as Güney took part in the Remakesploitation trend. Memduh Ün, who garnered early international notice for his film Kırık Çanaklar (The Broken Pots, 1960), also directed the Turkish James Bond rip off Altin Çocuk (Golden Boy, 1966) and, much later, Turkish Death Wish AKA Cellat (The Executioner, 1975). With the spotlight on the highly entertaining, low-budget escapism of Turkish Star Wars, it’s easy to overlook that Turkey, even in such adverse conditions, had no shortage of “respectable” films and, after a wilderness period from the early 1980s through into the 1990s, has resumed producing world-class films.

Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam is probably the most famous of the Turkish Remakesploitation films, by dint of having Star Wars as its template and because it so blatantly ripped off whole special effects shots and sequences. Truth be told, even though it cribs some broad ideas along with a bucket-load of special effects, it tells a distinctly different story than Star Wars and it is not even close to being the most thorough Rip-Off in this genre. Nor is Süpermen Dönüyor, even though Kunt Tulgar’s movie makes liberal use of stolen music cues and copyrighted characters. There are far more explicit offenders in this category, films that are practically shot-for-shot remakes of the originals. Crucially, none of them are authorised adaptations of the source material, distinguishing them from the standard and continuous back-and-forth nature of movie remaking across national borders.

Films belonging to the genre take a variety of forms, from those shot-for-shot remakes (Sevimli Frankeştayn AKA Turkish Young Frankenstein (Nejat Saydam, 1975)), to straight retellings adapted for a Turkish audience (Süpermen Dönüyor, Kunt Tulgar, 1979), to films that took elements of foreign films and incorporated them into ‘reimagined’ versions of the originals (Dünyayi Kurtaran Adam). All three types regularly feature in Top Ten Terrible Foreign Rip-Offs lists, their puny budgets, brazen appropriation and lunatic energy frequently compared ironically to their muscular Hollywood forebears. The common links between them are the international fame and success of their source material and a focus on any combination of action, sex, adventure and violence – the key constituents of any so-called B-movie and bread and butter for their contemporary domestic audience. The films were broad, easy to comprehend and entertaining to a fault – so no Turkish Chinatown, but Turkish Young Frankenstein was a no-brainer.

The films that can be described as part of the classic wave of Turkish Remakesploitation also belong to a larger genre of Turkish Fantastic Cinema. This term encompasses many kinds of genre films, from horror and science fiction to the hugely popular masked hero film. B-movies by any description and obscure to say the least, these films are not widely available even in Turkey, where the original prints have long since been sold off to television stations or simply disappeared entirely. Often the best sources for viewing them are VHS copies of pre-digital Turkish television broadcasts and/or German rental copies, ripped for the internet. Luckily and somewhat miraculously, a decade ago MTV Turkey began screening many of these films, previously believed to be lost altogether, in a weekly Fantastic Cinema slot. Otherwise, tiny independent companies like Onar Films, based in Greece, distributed DVD versions sourced from original prints. While these were lovingly packaged, carefully cleaned and prepared for release and much better quality than YouTube uploads, they were hampered by the extremely poor quality of the existing prints, which had never been high priorities for preservation or digital remastering.

From a modern, western perspective, cataloguing and delineating these films is a nightmare, due to a number of factors. First and foremost, the lack of an international audience even at the time means that the films and filmmakers have very little status in the west. Awareness of them now is really due to some hard work by fans of the genre(s) and a whole lot of wry internet ‘appreciation’. Even now, the documentation and availability of these films is very limited, automatically granting canonical status to a handful of high-visibility Rip-Offs – Turkish Star Wars, Turkish Superman and Turkish ET (Badi, Zafer Par, 1983) among them. The films that are available, one way or another, often have sub-standard English subtitles (with no disrespect to the efforts made, for which we have to be very thankful) and most have no English subtitles at all. Additionally, there seems to be very little behind-the-scenes information available and attempts to frame these films in any kind of context are very rare. Bill Barounis of Onar Films produced a helpful Turkish Fantastic Cinema Guide and while there are surely more scholarly tomes on the history of Turkish cinema, Fantastic or otherwise, they are, by and large, written in Turkish and in any case not widely available.

Fortunately, as the films of particular interest here have benefited from the widest modern audience, it’s still possible to discuss them in context and to trace their origins somewhat. While the key period for these films is the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, their roots go much further back. Prior to World War II, the Turkish film industry was dominated by a handful of companies importing foreign product into the major cities of Istanbul, Izmir and Ankara. After 1948, when the municipal tax on exhibition was reduced from 75% to 25% (leaving the tax on imported films at 70%), there was an explosion in domestically produced Turkish cinema. By the mid 1960s, Turkish cinema had expanded rapidly to become one of the biggest film making economies in the world, centred around Yesilçam (literally ‘Green Pine’ and named for a street in Istanbul that housed many production companies), which became a by-word for Turkish cinema in the same sense Hollywood is for classic American film.

However, while there were over 1,000 cinemas in Turkey at the peak of this wave, Hollywood product was still limited to theatres in the major cities and the coasts, leaving the huge Anatolian population in the south at a disadvantage – which is to say, there was a huge demand for the kind of westernised product epitomised in the Western and Action genres which was not being fully catered for. Starting around 1962, the Turkish Western became a hugely popular genre with 15 films a year being produced at the peak of the genre’s popularity in the 1970s and an audience happy to consume up to three films a day. In this period, the power of the regional distributors was paramount as they could and would demand films to their own specification, according to the discriminations of their local audiences. Unfortunately, due in part to the decentralisation of the system (with hundreds of companies making films), the general tilt was towards private enterprise, meaning that profits from films were not directed back into future film production, but removed for private gain. This was essentially a cash-flow business, with the success of one film providing the budget for the next, and one that could not sustain itself under any adversity. Eventually, Yesilçam’s output became dominated by soft-core porn productions.The encroachment of television and VHS meant that cinema revenue took a dive in the late 1970s and 1980s, which, in combination with that still thirsty-for-action Southern audience, created the perfect environment for Turkish Remakesploitation to thrive, albeit briefly.

Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam speaks to the audacity of some Turkish filmmakers, but the copyright situation in Turkey then is extremely vague from a modern perspective and it seems clear that there was no pertinent law of any kind in Turkey at that point. Indeed, there was a similar approach taken to the recording of foreign songs, at least up until the 1990s. At any rate, most of the films to be made in this golden age were well under Hollywood’s radar, probably more so than even Tarzan Istanbul’da (which had attracted the attention of Hollywood lawyers), and catered to an audience that had very little access to Hollywood product. Up until this point, it was standard practice in Yesilcam to freely adapt English-language novels, scripts and movie serials. There had been numerous Turkish bootlegs of Hollywood properties like The Lone Ranger, Zorro and Flash Gordon as well as oddities like Tosun and Yosun, the Turkish Laurel and Hardy clones, and innumerable Turkish Westerns. The spirit of the classic Turkish Remakesploitation can be traced in some of those Westerns, in their enthusiastic appropriation of American Western tropes and types (in similar fashion to the Italian Spaghetti Westerns), and their giddy disregard for international copyright concerns.

Una Pistola Per Ringo (Duccio Tessari, 1965), the now-classic Spaghetti Western, spawned many unauthorised spin-offs and unofficial sequels (as indeed it did in homeland of Italy). Similarly, Django (Sergio Corbucci, 1966) soon inspired the likes of Cango Olum Suvarisi (Django Rider Of Death, Remzi Conturk, 1967). Then came Çeko (Çetin Inanç, 1970), featuring a Turkish analogue of the Spaghetti Western anti-hero. Çeko opens with music stolen from Ennio Morricone’s score for The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (Sergio Leone, 1966) and goes on to utilise his Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968) score and Riz Ortolani’s music for Day Of Anger (Tonino Valerii, 1967). Even with the relatively low budget director Inanç had at his disposal, and the hasty production schedule – which would rapidly earn him the sobriquet “Regisör Jet”, the Jet Director – it was yet more economical to plagiarise pre-existing music. There were, of course, composers at work at the industry, but they would have cost too much, even in the form of the library music that they were most frequently employed to produce. With the materials at hand in the form of worn American prints and with impatient theatre owners on the phone, representing a waiting audience, directors like Inanç could churn out cheap copies quickly and to demand.

All of which begs the uncomfortable question of why filmmakers did not simply manufacture and distribute bootleg prints. The answer is in the question, and it is because these were filmmakers and not criminals. It seems clear that these films could not exist without a certain level of raw enthusiasm for the source material, the genres they represent and the filmmaking process itself. In any case, such blatant theft could easily be considered too likely to provoke the attention of litigious Hollywood studios that, after all, were still screening their product in the major cities, though they would not have a presence in the country as distributors until the 1990s. Equally probable is that the audience responded more enthusiastically to representations of these stories through a Turkish prism, which the filmmakers were only too eager to provide. It’s presumptuous and perhaps condescending to consider that the language barrier when screening original American films was an important element, but it likely would play a part. What is more than likely is that the significant delay between the initial American release and the widespread distribution of American films – even to the extent that they reached – provided a window ripe for exploitation.

Inanç is the most prominent behind-the-scenes character in the story of Turkish Remakesploitation. Weaned on the same comic books and serials that inspired his contemporaries Lucas and Spielberg, his first notable work was writing the screenplay for Kilink Istanbul’da (Yilmaz Atadeniz, 1967), a rip-off of Italian comic strip Killing, itself a rip-off of another called Kriminal, which was again a rip-off of Diabolik – making Kilink Istanbul’da a kind of bastard cousin to Danger: Diabolik (Mario Bava, 1968). His first film as director, Çelik Bilek (1967), was a Rip-Off of another Italian comic series, this time Il Grande Blek. After Çeko, he churned out carbon copies of Bonnie and Clyde, Dirty Harry, Mad Max, Jaws, First Blood, Rocky and Rambo II, making him by far the most prolific of the Remakesploitation directors. Those films, however, are only a sampling of the 136 films he made before moving into television in the mid 1980s. His transition then was emblematic of the general refocusing of the industry around television and its revenues in the 1980s and 1990s.

The key to understanding the films of Turkish Remakesploitation is to see them in context, not as part of a bungling criminal enterprise, but as the work of inventive, cash-strapped pragmatists. They were opportunists, certainly, but no more than Roger Corman or, indeed, any other Hollywood producer. The films were, after all, made for and enjoyed by an audience that could be described as undiscerning, but is more properly seen as enthusiastic, extremely receptive and, ultimately, forgiving, if the entertainment was worth the price of admission. There are comparisons to be drawn between Turkish Remakesplotiation and some Blaxsploitation (eg “The Black Exorcist” – Abby, William Girdler, 1974) in the way that mainstream (white, American) content is recreated but transformed to reflect the appearance and cultural specificity of the ‘niche’ audience. They’re also a worthy example of the hijacking and détournement of the Hollywood juggernaut to produce films for local consumption and, to a very limited extent, local profit. It’s hardly Robin Hood and it doesn’t beat a genuinely creative original and non-derivative industry, but it’s a lot more attractive, culturally, than simply swallowing what America doles out wholesale.

But their worth is not merely academic. And it’s not simply found in their superficial comic value, or even in their oddball energy, strange logic and generally singular approach to genre filmmaking. It’s in the spirit they were made in, the sheer will to make films overwhelming the paucity of available resources. It’s about making films of a certain kind when logic perhaps should tell you that you are not able to and not being constrained by your material limitations – certainly not when there is the prospect of expanding your material wealth. Fundamentally, Turkish Remakesploitation survives because it’s still doing what it was created to do – entertaining, even if that enjoyment sometimes takes the shape of snarky, ill-informed criticism.

Comparing the intent of Çetin Inanç and his contemporaries to their Hollywood counterparts is perhaps the most instructive measure. The cultural influences they share, taking for granted the international success of American comics and movie serials of the 1930s and 40s, seem as important as their distinct national identities. How different would the original Indiana Jones and Star Wars trilogies look if they were made with a fraction of the budget, talent pool, shooting schedule and basic infrastructure that they found in Hollywood? And though posterity has not been kind to the films of Turkish Remakesploitation, the smiles they engender and the basic thrills they offer are undiminished. As Kunt Tulgar has said, “Action and adventure never die in our culture.”

Sean Welsh

Remakesploitation Fest 2020 takes place 25-26/04/2020 at Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow. Tickets available from our online shop here. Keep up-to-date with the Facebook event page here.

NB This article was originally published in 2011 at physicalimpossibility.com. Thanks to Gokay Gelgec of the Sinematik website and the sadly departed Bill Barounis of Onar Films for invaluable background information on these films and the culture they were made in. Wherever possible, we’ve referred to the best-presented and ‘official’ versions of these films available.